High Jumper Erik Kynard Awarded Gold, Wrestler Tervel Dlagnev To Get Bronze From London 2012 Olympics

by Karen Rosen

Erik Kynard celebrates after winning the silver medal in the men's high jump final at the Olympic Games London 2012 on Aug. 7, 2012 in London.

Erik Kynard has never celebrated his silver medal from the Olympic Games London 2012. Tervel Dlagnev never had an Olympic medal to celebrate.

Now they are getting the recognition they always knew they deserved.

More than nine years later, Kynard is officially the gold medalist in the men’s high jump while Dlagnev is a freestyle wrestling bronze medalist in the 120 kg. division.

“It was kind of like, ‘Finally,’” said Kynard.

“It’s been so long, the emotions are drained from it,” said Dlagnev. “Obviously, at the time I was pretty hurt.”

Both Kynard, 30, and Dlagnev, 36, have known since 2019 that medals could be reallocated based on doping disqualifications. However, appeals, bureaucracy and the pandemic slowed down the process. The International Olympic Committee Executive Board made the decision earlier this month.

“I think the issue of drugs in sports is something that existed obviously before my career in Olympic sports, and it probably will exist after,” Kynard said. “I just hope that one day they find some system of due process that can actually reward properly athletes who are cheated and there’s some type of reparations besides just saying nine years later, ‘Hey, you’re the guy who really won.’”

In 2012, Kynard leaped 2.33 meters while Ivan Ukhov of Russia went 2.38 to beat him. Now Kynard is the gold medalist without leaving the ground.

Ukhov was banned in 2019 by the Court of Arbitration for Sport based on his country’s state-sponsored doping program. He was retroactively disqualified from the London Olympics.

Also in 2019, Artur Taymazov of Uzbekistan was stripped of his 2012 wrestling gold. The International Olympic Committee said he tested positive for a banned steroid when his sample was retested using more modern lab technology. Taymazov had previously forfeited his 2008 gold medal for the same reason, but retained his gold in 2004 and silver in 2000.

“The frustrating thing was everyone knew this guy was doping,” said Dlagnev. “We would ask the Russians, ‘Taymazov, doping?’ They’d say, ‘No no, very good vitamins’ and then they’d kind of laugh.”

When Dlagnev began hearing rumors in 2019 that a bronze medal was a possibility, he had mixed emotions. He had come to terms with his fifth-place finish.

“I beat Taymasov the year before in 2011 (at the world champiionships), so I was planning on winning the Olympics anyway,” Dlagnev said. “After I lost, it was kind of a bummer, but then you go on and that’s your story. You didn’t medal. And then this many years later you hear about it. There’s a little bit of frustration in it as far as, ‘That’s kind of scummy that he got away with it and it took this long,’ but I also appreciate the fact that they hunted it down and made it right.”

A Moment That Cannot Be Replaced

Yet both athletes say nothing can make up for what they missed in 2012. Kynard did not stand on the top step of the podium and Dlagnev didn’t make the podium at all or see the American flag raised in his honor.

“That’s not only a moment that was taken away from me, it’s something that was taken away from the entirety of my support system, family and friends,” said Kynard, who said his father and 74-year-old grandfather were in the stadium in London. “Nothing can replace that. It’s the greatest flaw in the system of the Olympic Movement.”

He said he had suspicions about Ukhov at the time, “but if you do say something, you’re a sore loser.”

While Kynard moved up from silver, two other Team USA athletes also saw their results change: Jamie Nieto is now fifth and Jesse Williams is tied for eighth.

In the women’s high jump, Chaunte Lowe is now fifth. She previously moved up to the bronze medal at the Olympic Games Beijing 2008.

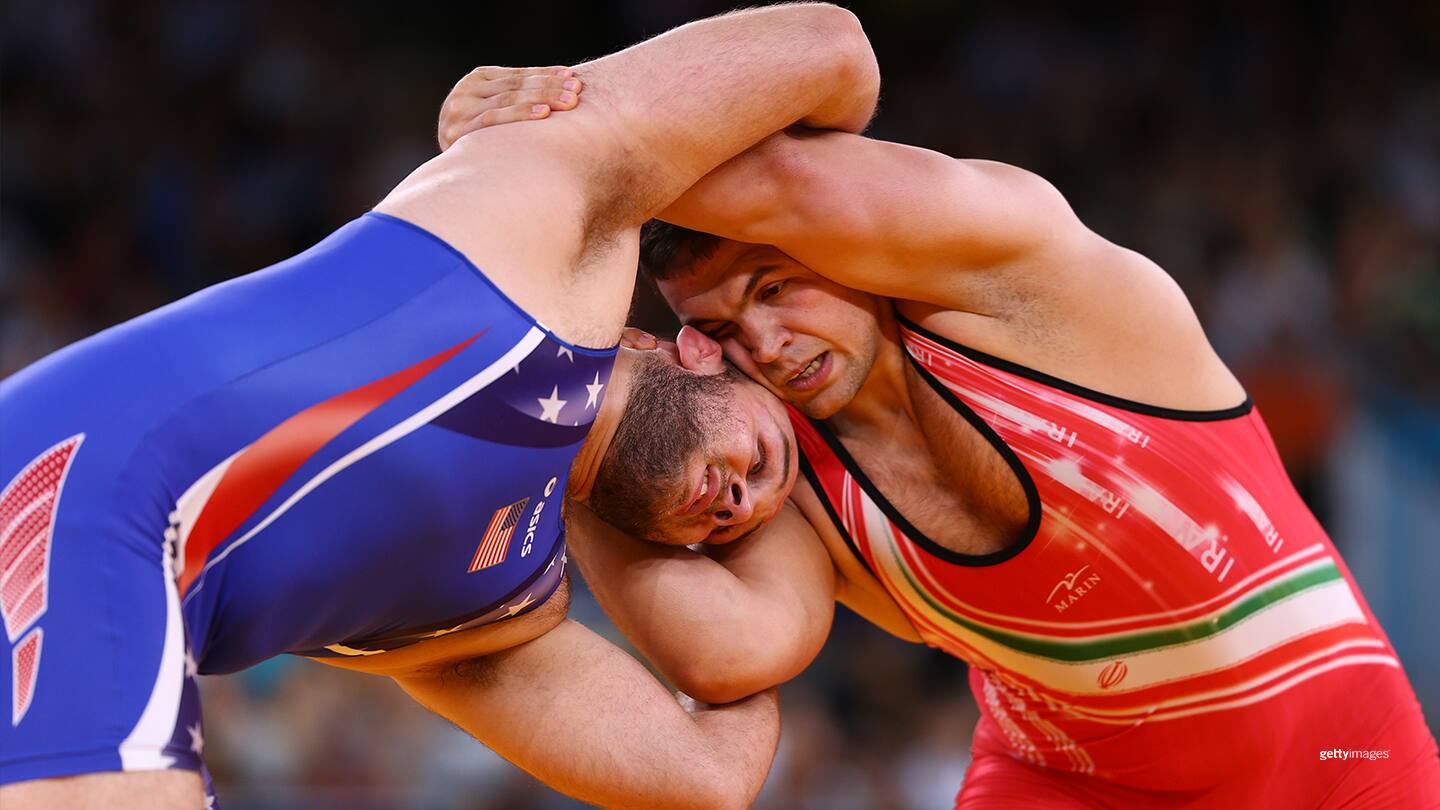

Tervel Dlagnev competes against Komeil Ghasemi (Iran) in the men's freestyle 120 kg. at the Olympic Games London 2012 on Aug. 11, 2012 in London.

Neither Kynard nor Dlagnev knows how or when they will receive their new medals.

Dlagnev, a two-time world championships bronze medalist and Pan American Games champion, said he has been told he has options: he could have a medal ceremony at the next Olympic Games, receive the medal in the IOC office in Switzerland, or coordinate with USA Wrestling to be honored at a domestic event. “Who knows? Maybe I’ll do it at a home dual at Nebraska,” said Dlagnev, who is a volunteer coach with the Cornhuskers’ wrestling team. “I don’t want to travel to Europe for decade-old medal.”

His wife Kirsten has some ideas. “She says we’re going to make me a podium and play the national anthem for me,” he said, “I probably won’t go through with it, but she’s all pumped up.”

Kynard said he has not been told about his options, but has already been in contact with USA Track & Field and the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee about receiving the difference in prize money between a gold and silver medalist.

While all athletes concerned are supposed to return their medals and diplomas for reallocation, those medals will not necessarily be passed down the line.

Kynard would be happier with a medal that did not have any fingerprints on it. “I don’t know what the one he had has been through,” he said.

Life Goes On

Neither athlete believes his life will change with the upgrade in Olympic results.

“It’s kind of like a full-circle moment,” Kynard said. “I was 21 years old. It’s like the man that I have been working my whole career to become and attain that level of greatness, I had already attained nine years ago.”

Kynard, who placed sixth at the Olympic Games Rio 2016, has not officially retired, but the NCAA champion from Kansas State said he is in a period of transition from the sport. Kynard is living in the Atlanta area and exploring career opportunities. With a degree in business, he is considering marketing, consulting, business administration or organizational leadership.

“I think my greatest work is still ahead of me in life,” Kynard said. “When I look back at it, receiving that announcement of being Olympic gold medalist nine years after the fact will not be the greatest announcement surrounding my legacy.”

Dlagnev said other people have been more excited than he was about his bronze medal. He received “a ton of texts” congratulating him and he was able to reconnect with people from his past.

“It’s a cool statistic – you’re in the conversation of an Olympic medalist,” Dlagnev said.

But he’s already where he wants to be as a wrestling coach at Nebraska. “The coaches trusted me, thought I was a good fit before I was a bronze medalist,” said Dlagnev, who was an NCAA Division II national champion for the University of Nebraska at Kearney, “so it’s not like I’m going to ask for a raise. I like where I am. I like what I’m doing.”

He believes the medal will have greater resonance for his kids, sons Isaiah, 8, and Titus, 7, who saw him compete at Rio, and 1-year-old daughter Maelynn.

“They’ll look back in history and see their dad was an Olympic medalist and we’ll have an Olympic bronze medal to play with.”

Or maybe more than one. Dlagnev was also fifth in Rio.

“That’s the joke now – don’t worry I’ll be a two-time Olympic medalist in a couple of years,” he said. “It’ll be interesting.”